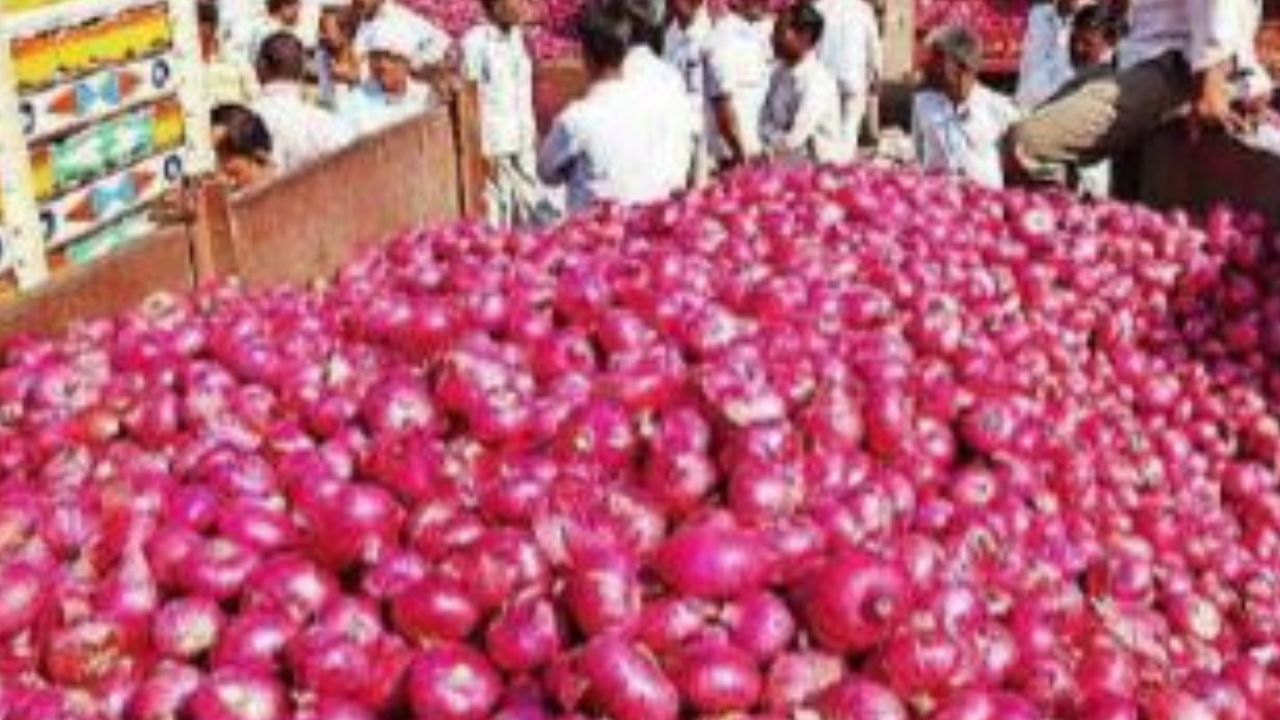

NEW DELHI: Rising onion prices in India pose a greater risk to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government than a recent spike of 700% in tomatoes, forcing authorities take fresh steps to contain food inflation before key polls.

India has imposed a 40% export tax on onions and plans to sell them locally at subsidized rates. The vegetable stands alongside tomatoes and potatoes as part of a trio of crops so crucial to Indian diets that past price spikes due to crop losses have prevented some ruling parties from returning to power. Consumers are more sensitive to onions — a vegetable that’s hard to be replaced with any other commodity in many local cuisines — than to tomatoes and potatoes.

The government faced fierce criticism after tomato prices rocketed as much as eight-fold following heavy rains in key growing areas. The cost of tomatoes has been falling, but a steady rise in onions put the authorities on high alert. The moves come as costs rise for many farm commodities, such as wheat and rice, because of poor weather.

Stable food prices are crucial for Modi, who will seek a third five-year term in national elections next year. Retail inflation is running at a 15-month high, underscoring the scale of the challenge. The government has curbed exports of wheat, rice and sugar, and may scrap a 40% tariff on wheat imports. It’s selling tomatoes and grain in the open market and curbed stockpiling of some crops.

“The government’s move on onions is preemptive in nature, as the price rise appears in line with seasonal trends for now,” said Rahul Bajoria, an economist with Barclays Bank Plc. “But with expectations of an erratic end to the monsoon season,” the government is focusing on the risk of food prices staying elevated in the coming months, he said.

El Niño threat

An El Niño-induced spell of poor weather may hurt onion crops in the top growing state of Maharashtra, where precipitation is already below average. Monsoon rains overall in India have been about 7% below normal, helping push up food prices. Wheat has risen 12% in Delhi from a year earlier. Rice costs 22% more, tomatoes are up 80%, while onions have increased 32%.

Amar Kisan Jagtap, 44, who grows corn and onions on his six acres of land in Maharashtra, skipped growing onions during the monsoon. Jagtap plans to halve the onion area during the winter season as he anticipates more curbs ahead of some state polls this year and the general election in April or May of 2024.

“I will reduce plantings as my costs are rising every year, but we’re not able to get remunerative prices,” Jagtap said in an interview. “The government’s interference is very high in onions and the recent move to impose an export duty will put pressure on prices.”

Maharashtra is the country’s top producer of onions, accounting for more than 40% of output. They are grown three times a year, twice in the rainy season and once during winter. Rains in parts of the state have been 18% below normal, stressing crops and making the government nervous ahead of the polls.

“Obviously, elections are in focus,” Bajoria said. The “bulk of the food price spike in July was driven by vegetables that are perishable and seasonal in nature,” he said. “I would be more concerned about commodities such as rice and wheat that tend to be more sticky.”

India has imposed a 40% export tax on onions and plans to sell them locally at subsidized rates. The vegetable stands alongside tomatoes and potatoes as part of a trio of crops so crucial to Indian diets that past price spikes due to crop losses have prevented some ruling parties from returning to power. Consumers are more sensitive to onions — a vegetable that’s hard to be replaced with any other commodity in many local cuisines — than to tomatoes and potatoes.

The government faced fierce criticism after tomato prices rocketed as much as eight-fold following heavy rains in key growing areas. The cost of tomatoes has been falling, but a steady rise in onions put the authorities on high alert. The moves come as costs rise for many farm commodities, such as wheat and rice, because of poor weather.

Stable food prices are crucial for Modi, who will seek a third five-year term in national elections next year. Retail inflation is running at a 15-month high, underscoring the scale of the challenge. The government has curbed exports of wheat, rice and sugar, and may scrap a 40% tariff on wheat imports. It’s selling tomatoes and grain in the open market and curbed stockpiling of some crops.

“The government’s move on onions is preemptive in nature, as the price rise appears in line with seasonal trends for now,” said Rahul Bajoria, an economist with Barclays Bank Plc. “But with expectations of an erratic end to the monsoon season,” the government is focusing on the risk of food prices staying elevated in the coming months, he said.

El Niño threat

An El Niño-induced spell of poor weather may hurt onion crops in the top growing state of Maharashtra, where precipitation is already below average. Monsoon rains overall in India have been about 7% below normal, helping push up food prices. Wheat has risen 12% in Delhi from a year earlier. Rice costs 22% more, tomatoes are up 80%, while onions have increased 32%.

Amar Kisan Jagtap, 44, who grows corn and onions on his six acres of land in Maharashtra, skipped growing onions during the monsoon. Jagtap plans to halve the onion area during the winter season as he anticipates more curbs ahead of some state polls this year and the general election in April or May of 2024.

“I will reduce plantings as my costs are rising every year, but we’re not able to get remunerative prices,” Jagtap said in an interview. “The government’s interference is very high in onions and the recent move to impose an export duty will put pressure on prices.”

Maharashtra is the country’s top producer of onions, accounting for more than 40% of output. They are grown three times a year, twice in the rainy season and once during winter. Rains in parts of the state have been 18% below normal, stressing crops and making the government nervous ahead of the polls.

“Obviously, elections are in focus,” Bajoria said. The “bulk of the food price spike in July was driven by vegetables that are perishable and seasonal in nature,” he said. “I would be more concerned about commodities such as rice and wheat that tend to be more sticky.”

timesofindia.indiatimes.com

Source link